Emily Beausoleil

University of British Columbia

The recent piranhic media frenzy surrounding Wikileaks and its founder Julian Assange almost immediately calls to mind the Pentagon Papers leaked exactly 40 years ago; where, though a mere 7,000 Xeroxed documents compared to Wikileaks’ hundreds of thousands, the government claimed the damage to national security was so great that it required stopping the presses – an order thankfully overruled by the Supreme Court and dismissed by seventeen newspapers; where the Espionage Act was first used as an Official Secrets Act, for which it was never intended; where the government similarly demanded the ‘return of information’; and where Ellsberg was likewise accused of treason rather than patriotism.

And just as in Ellsberg’s case, too, the contents of this year’s July leak was found, as described in a recently released Pentagon letter, not to compromise security in any way, despite claims by US Secretary Robert Gates and Joint Chief of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen, among others, that Assange and his team had ”blood on their hands.”

University of British Columbia

The recent piranhic media frenzy surrounding Wikileaks and its founder Julian Assange almost immediately calls to mind the Pentagon Papers leaked exactly 40 years ago; where, though a mere 7,000 Xeroxed documents compared to Wikileaks’ hundreds of thousands, the government claimed the damage to national security was so great that it required stopping the presses – an order thankfully overruled by the Supreme Court and dismissed by seventeen newspapers; where the Espionage Act was first used as an Official Secrets Act, for which it was never intended; where the government similarly demanded the ‘return of information’; and where Ellsberg was likewise accused of treason rather than patriotism.

And just as in Ellsberg’s case, too, the contents of this year’s July leak was found, as described in a recently released Pentagon letter, not to compromise security in any way, despite claims by US Secretary Robert Gates and Joint Chief of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen, among others, that Assange and his team had ”blood on their hands.”

Certain differences present themselves, of course: where Nixon worked covertly via the order for a dozen Bay of Pigs veterans to “incapacitate Ellsberg totally,” now Democratic Party consultant Bob Beckel can call for the illegal assassination of Assange on public television, as President Obama’s administration makes moves to create an explicit Official Secrets Act. But like the Pentagon Papers so long ago, Wikileaks has, in the words of an international group of former intelligence officers and ex-government officials who wrote in support of Assange, “teased the genie of transparency out of a very opaque bottle, and powerful forces in America, who thrive on secrecy, are trying desperately to stuff the genie back in.”

our leaders aspire to, and have for a long time.”

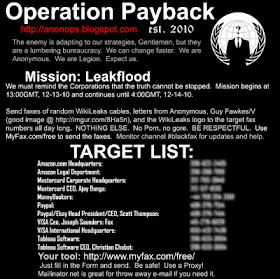

But what is striking about this recent case of disclosure is the difference in public response: compared to the public outcry of the 1970s, which ignited protest, fuelled a social movement, and catalyzed the end of the Vietnam War, the public is strangely silent in 2010. Well, not silent, surely – but rather than an eye for the content of these released documents and their implications for democratic transparency and government accountability, all eyes are on Assange, this striking figure stepping on the world stage and the concomitant personal scandal that erupted with impeccable timing; all eyes are on the guerrilla warfare waged in cyberspace between Anonymous and various corporations. Even the accused original source, Bradley Manning, who has been in prison since May, receives his share of media coverage, though the messenger has far more been the target. But with the exception of the New York Times, the actual deceptions revealed by these documents have been all but abandoned by the US media, and likewise public response has been a resounding shrug.

We’ve gotten pretty good at shrugging, in liberal democracies. A negative definition of freedom helps, of course, construed as the right to be left-the-heck-alone. And since western world leaders saw the atrocities the everyman was capable of during World War One, such passivity has been at times actively cultivated, beginning most famously with the work of Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud and originator of the field of public relations, who was employed by corporations and the US government alike to use marketing strategies to siphon this dangerous energy into safer channels. Indeed, Carol Pateman made clear some years ago how such democracies function through, rather than in spite of, the passivity of the majority of the population. What kind of stability, what kind of continuity, could be assured after all, if politics had to make room for the torrent of people who presently feel there is no point? Martin Luther King Jr. makes a similar observation regarding the political power of inaction when he writes from Birmingham Jail that “the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice;...who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a ‘more convenient season’.”

But what strikes me about this recent shrug to political deception is how it reveals a general acceptance of lying in politics. We know, don’t we? Are we surprised? The lying in politics that Arendt identified as a core threat to democracy, whether through conscious concealment or unconscious ‘defactualization’ via fidelity to theory, seems now to be only one aspect of, as Raymond Williams first coined it, a “dramatized society.” We live in a culture where the line between performance and reality, between artifice and authenticity, between politics and popular culture has become increasingly blurred. Where identities are cultivated like manicured gardens on facebook, where news stations parade their bias and peddle infotainment, where ‘reality shows’ are clearly staged, where a comedian testifies in character to the Supreme Court and an actor lives and breathes the role of a untalented rapper for two years, where bands are formed around boardroom tables and elaborate hair products can give you that unkempt look, where hipster ‘irony’ comes full circle to earnestness the longer one’s nonchalance is honed and insouciant moustache remains intact. We live in a culture of explicit artifice, and, like the Cubists who were arguably the first to draw explicit attention to the surface within their work, we are aware, very aware, of how much the medium is the message. And yet, as opposed to the Cubists, perhaps, this general awareness of and conscious play with surface is itself somehow less earnest – as if, rather than unveiling a latent truth or essential core, it’s turtles all the way down. In the face of acknowledged artifice, it seems a natural response to cultivate studied indifference and a world-weary arch of the eyebrow. As any middle-schooler will tell you, it’s better to opt out than be the fool.

This movement to a culture of explicit artifice is paralleled, interestingly, in the world of US cinema, which moved from Method acting’s earnest soul-searching and commitment to the ‘gritty truth’ by actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean post-WW2 – where actors were in therapy as a matter of course and playing Blanche Du Bois almost drove Vivien Leigh insane – to what film historian David Thomson calls “cool pretending” that defines current cinema acting, epitomized by Meryl Streep and George Clooney, where one has a sense the character leaves no traces once the role is cast aside; indeed, that actors are not quite fooled by their own performance, and you have been let in on the joke.

The pledge to sincerity and emotional truth that defined Method acting have been replaced by a predominance of deft skill and “naked pretense” (which, Thomson says, “you could call...lying, as much as acting”), founded on “a way of looking at the world that says you can't trust anyone, can you? It suggests that—for the moment at least—we have given up on self-knowledge and feel ourselves being massaged or directed by most of our presidents, and nearly all of our eternal performers from Johnny Carson to David Letterman... Presidents move us from time to time, just as hosts make us smile, but most of them warn us that we're in a play or a game.” Such is the contemporary condition in liberal democracies, where sincerity is suspicious and earnestness appears ironic, if not tragic-comedic.

In a culture where the line between reality and performance is unclear and constantly on the move, it is no wonder, perhaps, that the vocabulary of recent presidential debates has been lowered to a sixth-grade level in response to common conflations of eloquence with insincerity. It is no wonder, perhaps, that comedian John Gnarr is Reykjavik’s latest mayor, and platform promises of a polar bear display at the zoo, free towels at public swimming pools, and coalitions only with parties who have watched all seasons of “The Wire” are more earnest than they first appear. And it seems perfectly appropriate that comedians hold a political rally to restore sanity, while the rise of flash mobs across the western world invokes and enacts a public sphere formerly reserved for public protest – fleeting publics and collective acts now simply for their own sake, as if the performance itself provided a sense of concrete experience and sincere collective that are otherwise absent. Perhaps these performances are an unlikely source of a surrogate ‘authenticity’ – at the very least, they provide respite by explicitly naming the predominance of veneer that is often as obvious as it is undeclared.

Part of this movement towards explicit artifice is part and parcel of an increasing reflexivity regarding the situated nature of all knowledge-claims, the partiality of perspective – from anthropologists and theorists to jazz musicians, scientists and performance artists, responses to the dangers inherent to claims of ‘authenticity’ and ‘neutrality’ and the ethical obligation to acknowledge the performance within every account have been broad and diverse. And part of this is also, at times explicitly, a response to the lack of such humility within current polemics and fundamentalisms – refusals to, in William Connolly’s terms, “insert a stutter in one’s faith,” that have recently fuelled such vitriol and fear, inhibited reflection, and cultivated new enemies where once were none – perhaps this movement to explicit artifice is a response, if not a conscious call, to calm down, take a deep breath, and count to ten. At the very least, to take a closer look at the medium of the message.

But one effect of this culture of explicit artifice seems to be a contribution to the politics of inaction. As opposed to the public outcry of the 1970s after the release of the Pentagon Papers that belied a faith in political sincerity and media objectivity now betrayed, we have no such faith. Hence the absence of collective moral outrage, for the fact is that we know we are being deceived; and, in the passing of time and as the facticity of deception becomes one reliable truism, we’re no longer ‘mad as hell’, and yes, I suppose, we’ll take it for a little more.

Shielded by ironic distance and a rueful grin, armed with sarcasm and a noncommittal shrug, we acknowledge the pervasiveness of veneer, and clear-sighted rather than wide-eyed, we are in on the ruse; we may not know what lies behind it, but at least we recognize the pageantry. We may not know where to direct our dissatisfactions or how to give effective shape to a creeping sense that things are not as they should be, but at least we can’t be called naive. We’re in on the joke, no? Isn’t that something?

This general acknowledgement of artifice that courses through all levels and arenas of contemporary western culture need not only lead to inaction – as comedians-cum-unlikely-heroes and flash mobs make clear, the performative nature of everyday life might itself offer latent possibilities for collective action. While the potential directions for such collective awareness are rhizomatic and undetermined, I wonder what forms of action might emerge in the absence of recourse to ‘sincerity’ as such – or if, indeed, sincerity might be recuperated, in some form, in the process. This challenge brings to mind another: making “one’s life a work of art,” as Nietzsche and Foucault describe it, requires both brutal honesty regarding the artifice of one’s life and commitment to it nonetheless – both clear-sighted and wide-eyed, somehow. A moving target of a goal, far removed from either entrenched fundamentalisms or evasive apathy. But perhaps it signals a possible, if tenuous, if elusive, model we have yet to recognize in response to a culture of artifice; that, rather than a politics of inaction, such artifice carries with it an ethical demand that is not grounded on essential identity or universal truth, but something else...something else...Damn, it moved.

No comments:

Post a Comment