John Buell is a columnist for The Progressive Populist and a faculty adjunct at Cochise College. His most recent book is Politics, Religion, and Culture in an Anxious Age.

When liberals, progressives, or leftists of any stripe criticize our contemporary economic order, they are accused of class war. They are rebuked with the claim that gaps in income and wealth reflect the operations of the market and are therefore fair. Both of these contentions are false. Unfortunately American democracy has failed to address these falsehoods and in fact contributes mightily to inequities it is committed to address. Our democracy’s failings and the classic and modern theoretical perspectives that might mitigate these are the subject of a provocative new book by Steven Johnston, American Dionysia: Violence, Tragedy, and Democratic Politics.

If there is a class war, it is one being waged on behalf of the wealthy. Its vehicles are law, federal and state courts, administrative agencies, state and federal legislatures, and the corporate media. The ideology governing this class war is called neoliberalism. Perhaps the most obvious instance of this neoliberal agenda is the Trans Pacific Partnership. Though purportedly a “market friendly” instrument, one of its central goals is to achieve protected status for patents and trademarks. Nations that strive to make medication more affordable by providing generic drugs would be subject to countervailing suits and huge damage judgments. Similarly, banking regulations, more strict in many of our foreign competitors, would be reduced to the lowest common denominator. As for labor unions, even though the agreement purportedly contains some language about the right to organize, there is no enforcement means parallel to those regarding patents and copyrights. So much for the argument that these agreements should not interfere with domestic politics. Such interference is acceptable, even to be encouraged, when “intellectual property” is involved.

These legal and political structures lie at the heart of income and wealth inequality. Yet even these phrases sugar coat the state’s real impact. Johnston avoids the cool euphemisms. Neolliberalism maims and kills. It takes citizens in both the developed and especially the developing world. When financial markets collapse, houses are foreclosed on and families risk homelessness, especially as rental costs escalate. Healthcare denied leaves citizens to die.

Though a variety of liberals, socialists, social democrats may with good reason blame corporate capitalists, their think tanks, and their massive and self-reinforcing political contributions for neoliberalism’s casualties, democratic majorities both today and from our very founding should not be exempted from responsibility.

For starters, the market in land that bolstered a middle class society was founded in violence against Native Americans, takings that have never been adequately compensated. Even the Constitution stood as no barrier to exploitation of Native peoples. As Andrew Jackson replied to a Supreme Court decision supporting Native American land claims: “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” These takings represented more than a redistribution of property. The settlers eradicated native systems of land use and tenure. These were not recognized as legitimate because they did not conform to emerging bourgeois notions of land as a commodity that could be exploited, bought and sold. Then, as Johnston puts it, “the nation to be secured its freedom thanks, at least in part, to weapons purchased by the wealth slavery generated.”

To Johnston’s analysis I would add that further economic reforms, including general laws of incorporation, and limited liability helped turn a society that used markets into a market society, one in which land, labor, and money itself were treated as speculative commodities.

Johnston suggests US citizens need not only reforms that would challenge these market consolidations but more broadly a new counter-class war. History provides some potent examples—such as the Roman Tribunate, an institution giving Rome’s poorer citizens the ability to block legislation that would harm them. Finally we need a new democratic ethos, one informed by a tragic vision that recognizes democracy’s limits.

Democracy is caught in several related paradoxes. It promises much but given its exacting standards it cannot deliver. It thus produces periodically inordinate resentments.

Given its commitments to mutual self-rule, equality, it suggests a brand new day in politics. Democracy seems content to allow patriotism free reign insofar as patriotism obscures the tragic dynamics that bedevil it. Democracies see themselves as uniquely vulnerable and resort to tactics worthy of their enemies. Abuses are considered incidental, regrettable, and correctible, thanks in part to democracy’s reigning principles, especially procedural norms. Can theorists and activists fashion an ethos and practice that will address these systematic injustices?

Recasting Democracy

With its overarching confidence in itself, democracies often produce dubious outcomes in emergency situations. Often these emergencies are consequences of policies pursued by elites and then subsequently inflated in the mainstream corporate media. Or they are manufactured by elites in support of the reigning ideology. Think: the Gulf of Tonkin.

Steven Johnston, author of American Dionysia, provides a powerful reminder of democracy’s systematic faults, but he is no anti-democrat. His goal is to articulate and defend a tragic sensibility that might enable a more sustainable and mature democracy, one that would inflict less harm on its own citizens as well as the world. Democratic life involves taking on the burdens of success. Success mandates the continuation of politics because victory is made possible by those who suffer defeat, loss, injury and death. Injury is inevitable and unavoidable. It does not necessarily result from evil intentions. It “flows from the incompatibility of equally worthy goals… from the injustice that justice often entails, the unpredictable character of action in concert, and the stubborn nature of things.”

Such a sensibility engenders and is engendered by a view of the nature of the cosmos. The world is a “difficult, forbidding, uncertain, volatile, resistant, dangerous, and lethal” place. He adds: “A world so composed must be navigated with care and concern.”

Tragedy properly understood does not foster resignation but rather new bursts of creative energy. We act knowing that success and failure await us, but failure itself creates new options and possibilities.

Democracy must be forced to reflect on itself, which can be done though both through new memorials and rituals. Several imaginative examples, inspired by both classical tragedy and contemporary culture are presented. Thus, following from some of Rousseau’s institutional suggestions, Johnston advocates an annual reparations assembly mandated by law. This assembly would be duty-bound to hear the grievances of citizens who have been harmed by politics. Though such as assembly might well become an occasion for wealthy landowners, real estate developers, and financial tycoons to trumpet the harms of redistribution, even the most thoughtful reforms can be carried out with needless cruelty and have unintended consequences. In any case such an assembly today is hardly likely to strengthen resistance to egalitarian redistribution, and since many income disparities today are the result of state action rather than pure free markets it will give the voices of egalitarianism more opportunities.

Reparations assemblies might have changed some of our troubled history. I am led to ponder the fate of those who once engaged in what are now almost universally recognized as evil pursuits. Reparations assemblies might have serve as a kind of truth and reconciliation commission. Following the Civil War, union soldiers received pensions. Those who fought for the Confederacy received no such benefits, and their taxes helped fund these pensions. This benefit of course was denied to slaveholders, but most of the Confederate soldiers were not slave owners and often suffered in competition with slave labor. What might our history have been like if at some point such an assembly had awarded generous pension to former slaves and at least modest amounts, to poor and working class veterans of the Confederacy. Would these citizens been so easily recruited for Kevin Phillips' southern strategy?

Democracies need to curb their foreign abuses as well. Democracies must make the effort to see themselves though the eyes of the enemy. He suggests placing a commemorative plaque including the names of the perpetrators at the site of 9/11. When Americans look up at the site of the rubble they may have more of a sense of what others see when they think of us.

In what is likely to be at least as controversial, Johnston argues for a reassessment of the relation between violence and democracy. Violence and democracy are usually seen as antithetical. Yet contemporary democracy practices violence on a daily basis. Equally our democracy, which purports to be the world’s example, was founded in violence against both property and people. What were the original Tea Partyers but precursors of today’s much- reviled “looters” and “takers?” Though nonviolence is often portrayed as the key to the success of the Civil Rights movement, the threat of violence helped create an incentive to deal with these protests, just as the threat of violence encouraged Roman patricians to accept the institution of the Tribunate. Johnston is not advocating any shoot out with highly militarized police, but there may be situations in which strategic violence, violence that would not spiral out of control, could avert even far greater death.

I would add two points. Even nonviolence is not as pure as it purports. Reinhold Niebuhr pointed out in Moral Man and Immoral Society that even such nonviolent actions as blocking a train could deny needed food to those at the end of the line. He also added that the success of nonviolence depended on the moral ideals of those on the receiving end.

In today's continuing rush to foreclosure on delinquent mortgages the Occupy movement in cities as diverse as Atlanta and Detroit has engaged in actions designed to prevent foreclosures. In escalating rental markets, these actions might evolve into citizen patrols that would forcefully resist evictions. Violence might flow from such encounters, but the public attitude would not necessarily treat these patrols as disreputable lawbreakers. And how would local governments react? One who has imbibed a tragic view of politics realizes there is no certain answer. We can thank Steven Johnston for making these questions clearer and more pressing.

When liberals, progressives, or leftists of any stripe criticize our contemporary economic order, they are accused of class war. They are rebuked with the claim that gaps in income and wealth reflect the operations of the market and are therefore fair. Both of these contentions are false. Unfortunately American democracy has failed to address these falsehoods and in fact contributes mightily to inequities it is committed to address. Our democracy’s failings and the classic and modern theoretical perspectives that might mitigate these are the subject of a provocative new book by Steven Johnston, American Dionysia: Violence, Tragedy, and Democratic Politics.

If there is a class war, it is one being waged on behalf of the wealthy. Its vehicles are law, federal and state courts, administrative agencies, state and federal legislatures, and the corporate media. The ideology governing this class war is called neoliberalism. Perhaps the most obvious instance of this neoliberal agenda is the Trans Pacific Partnership. Though purportedly a “market friendly” instrument, one of its central goals is to achieve protected status for patents and trademarks. Nations that strive to make medication more affordable by providing generic drugs would be subject to countervailing suits and huge damage judgments. Similarly, banking regulations, more strict in many of our foreign competitors, would be reduced to the lowest common denominator. As for labor unions, even though the agreement purportedly contains some language about the right to organize, there is no enforcement means parallel to those regarding patents and copyrights. So much for the argument that these agreements should not interfere with domestic politics. Such interference is acceptable, even to be encouraged, when “intellectual property” is involved.

These legal and political structures lie at the heart of income and wealth inequality. Yet even these phrases sugar coat the state’s real impact. Johnston avoids the cool euphemisms. Neolliberalism maims and kills. It takes citizens in both the developed and especially the developing world. When financial markets collapse, houses are foreclosed on and families risk homelessness, especially as rental costs escalate. Healthcare denied leaves citizens to die.

Though a variety of liberals, socialists, social democrats may with good reason blame corporate capitalists, their think tanks, and their massive and self-reinforcing political contributions for neoliberalism’s casualties, democratic majorities both today and from our very founding should not be exempted from responsibility.

For starters, the market in land that bolstered a middle class society was founded in violence against Native Americans, takings that have never been adequately compensated. Even the Constitution stood as no barrier to exploitation of Native peoples. As Andrew Jackson replied to a Supreme Court decision supporting Native American land claims: “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” These takings represented more than a redistribution of property. The settlers eradicated native systems of land use and tenure. These were not recognized as legitimate because they did not conform to emerging bourgeois notions of land as a commodity that could be exploited, bought and sold. Then, as Johnston puts it, “the nation to be secured its freedom thanks, at least in part, to weapons purchased by the wealth slavery generated.”

To Johnston’s analysis I would add that further economic reforms, including general laws of incorporation, and limited liability helped turn a society that used markets into a market society, one in which land, labor, and money itself were treated as speculative commodities.

Johnston suggests US citizens need not only reforms that would challenge these market consolidations but more broadly a new counter-class war. History provides some potent examples—such as the Roman Tribunate, an institution giving Rome’s poorer citizens the ability to block legislation that would harm them. Finally we need a new democratic ethos, one informed by a tragic vision that recognizes democracy’s limits.

Democracy is caught in several related paradoxes. It promises much but given its exacting standards it cannot deliver. It thus produces periodically inordinate resentments.

Given its commitments to mutual self-rule, equality, it suggests a brand new day in politics. Democracy seems content to allow patriotism free reign insofar as patriotism obscures the tragic dynamics that bedevil it. Democracies see themselves as uniquely vulnerable and resort to tactics worthy of their enemies. Abuses are considered incidental, regrettable, and correctible, thanks in part to democracy’s reigning principles, especially procedural norms. Can theorists and activists fashion an ethos and practice that will address these systematic injustices?

Recasting Democracy

With its overarching confidence in itself, democracies often produce dubious outcomes in emergency situations. Often these emergencies are consequences of policies pursued by elites and then subsequently inflated in the mainstream corporate media. Or they are manufactured by elites in support of the reigning ideology. Think: the Gulf of Tonkin.

Steven Johnston, author of American Dionysia, provides a powerful reminder of democracy’s systematic faults, but he is no anti-democrat. His goal is to articulate and defend a tragic sensibility that might enable a more sustainable and mature democracy, one that would inflict less harm on its own citizens as well as the world. Democratic life involves taking on the burdens of success. Success mandates the continuation of politics because victory is made possible by those who suffer defeat, loss, injury and death. Injury is inevitable and unavoidable. It does not necessarily result from evil intentions. It “flows from the incompatibility of equally worthy goals… from the injustice that justice often entails, the unpredictable character of action in concert, and the stubborn nature of things.”

Such a sensibility engenders and is engendered by a view of the nature of the cosmos. The world is a “difficult, forbidding, uncertain, volatile, resistant, dangerous, and lethal” place. He adds: “A world so composed must be navigated with care and concern.”

Tragedy properly understood does not foster resignation but rather new bursts of creative energy. We act knowing that success and failure await us, but failure itself creates new options and possibilities.

Democracy must be forced to reflect on itself, which can be done though both through new memorials and rituals. Several imaginative examples, inspired by both classical tragedy and contemporary culture are presented. Thus, following from some of Rousseau’s institutional suggestions, Johnston advocates an annual reparations assembly mandated by law. This assembly would be duty-bound to hear the grievances of citizens who have been harmed by politics. Though such as assembly might well become an occasion for wealthy landowners, real estate developers, and financial tycoons to trumpet the harms of redistribution, even the most thoughtful reforms can be carried out with needless cruelty and have unintended consequences. In any case such an assembly today is hardly likely to strengthen resistance to egalitarian redistribution, and since many income disparities today are the result of state action rather than pure free markets it will give the voices of egalitarianism more opportunities.

|

| Desmond Tutu |

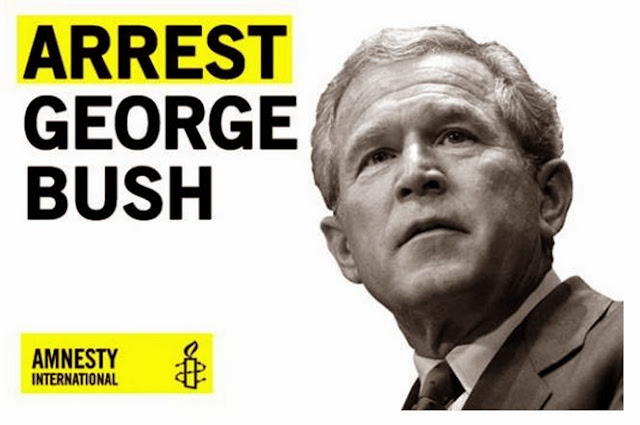

Democracies need to curb their foreign abuses as well. Democracies must make the effort to see themselves though the eyes of the enemy. He suggests placing a commemorative plaque including the names of the perpetrators at the site of 9/11. When Americans look up at the site of the rubble they may have more of a sense of what others see when they think of us.

In what is likely to be at least as controversial, Johnston argues for a reassessment of the relation between violence and democracy. Violence and democracy are usually seen as antithetical. Yet contemporary democracy practices violence on a daily basis. Equally our democracy, which purports to be the world’s example, was founded in violence against both property and people. What were the original Tea Partyers but precursors of today’s much- reviled “looters” and “takers?” Though nonviolence is often portrayed as the key to the success of the Civil Rights movement, the threat of violence helped create an incentive to deal with these protests, just as the threat of violence encouraged Roman patricians to accept the institution of the Tribunate. Johnston is not advocating any shoot out with highly militarized police, but there may be situations in which strategic violence, violence that would not spiral out of control, could avert even far greater death.

I would add two points. Even nonviolence is not as pure as it purports. Reinhold Niebuhr pointed out in Moral Man and Immoral Society that even such nonviolent actions as blocking a train could deny needed food to those at the end of the line. He also added that the success of nonviolence depended on the moral ideals of those on the receiving end.

In today's continuing rush to foreclosure on delinquent mortgages the Occupy movement in cities as diverse as Atlanta and Detroit has engaged in actions designed to prevent foreclosures. In escalating rental markets, these actions might evolve into citizen patrols that would forcefully resist evictions. Violence might flow from such encounters, but the public attitude would not necessarily treat these patrols as disreputable lawbreakers. And how would local governments react? One who has imbibed a tragic view of politics realizes there is no certain answer. We can thank Steven Johnston for making these questions clearer and more pressing.