Neal A. Maxwell Chair in Political Theory, Public Policy, and Public Service, University of Utah

In July Bill Connolly published a manifesto entitled “Toward an Eco-Egalitarian University.” I would like to complement his call for educational reinvention and resistance to the “neoliberal machine” by addressing selected aspects of the sports-violence-money-media-entertainment complex that governs and plagues so many of America’s colleges and universities. There are a number of issues here.

1) Major men’s college football and basketball programs serve primarily as minor league training academies for the NFL and NBA. This self-selected subservient role, highly profitable to some schools, financially problematic to many more, comes at the expense of the academic and moral integrity of the institutions implicated. As recent events at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill indicate, schools will not hesitate to corrupt their basic academic functioning, including manufacturing imaginary courses and bogus grades, to keep mercenary athletes eligible and turnstiles rotating.

2) These programs

generate tens of billions of dollars in revenues for themselves and other

dominant corporate players (broadcasters, apparel companies, the auto and beer

industries, etc.) in the neoliberal capitalist arena while exploiting the

non-union labor of (mostly) teenagers. Thousands of students on athletic

scholarships, so-called student athletes, are effectively the fulltime employees of colleges and universities who control their lives and can dismiss them at

will.

3) Football and basketball coaches are often the highest paid employees at their institutions with compensation packages—totaling millions—exceeding even the most lavishly paid college and university presidents. This warped financial structure informs students, who incur unsustainable debt to pursue the American dream, and professors, who may never be able to afford retirement, of their value in the so-called academic world.

4) Running a

football program means, by definition, that colleges and universities are

co-conspirators in a corrupt enterprise that sacrifices the short- and

long-term health and well-being of its participants. Morally, if not legally,

this amounts to felony assault and battery. Players may or may not be removed from games even when they are obviously damaged from routine plays.

Statistically, the vast majority of college football players will never play at

the professional level, which means they are sacrificing themselves for, at

best, an illusion.

5) Major sports programs are commonly linked to a culture of privilege and entitlement, which includes violence against women, a seriously underreported phenomenon, as the Florida State examples demonstrate. It might be convenient to presume that this is the isolated conduct of a few malefactors with a disposition to violence they brought with them to college, though it’s perhaps just as likely that they cultivated and extended the pleasures of domination and violence the sport teaches them and celebrates.

6) When football players at Northwestern initiated a unionization drive in order to protect themselves and their interests against their employer, the university, aided and abetted by the head coach, and concerned about possible repercussions to its bottom line, waged a concerted campaign to defeat them. To my knowledge, not one college or university president spoke in favor of the players’ autonomy and self-determination. Rather, they were determined to keep them in their properly subjected position.

Still, let us suppose, against the evidence, that Trustees and Presidents are serious when they talk about student athletes and seek to really fold sports into the intellectual life of a college or university. Well, here are some things they would do with respect to basketball.

For programs it will mean:

In July Bill Connolly published a manifesto entitled “Toward an Eco-Egalitarian University.” I would like to complement his call for educational reinvention and resistance to the “neoliberal machine” by addressing selected aspects of the sports-violence-money-media-entertainment complex that governs and plagues so many of America’s colleges and universities. There are a number of issues here.

1) Major men’s college football and basketball programs serve primarily as minor league training academies for the NFL and NBA. This self-selected subservient role, highly profitable to some schools, financially problematic to many more, comes at the expense of the academic and moral integrity of the institutions implicated. As recent events at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill indicate, schools will not hesitate to corrupt their basic academic functioning, including manufacturing imaginary courses and bogus grades, to keep mercenary athletes eligible and turnstiles rotating.

|

| A UNC-Chapel Hill student athlete's paper. |

3) Football and basketball coaches are often the highest paid employees at their institutions with compensation packages—totaling millions—exceeding even the most lavishly paid college and university presidents. This warped financial structure informs students, who incur unsustainable debt to pursue the American dream, and professors, who may never be able to afford retirement, of their value in the so-called academic world.

|

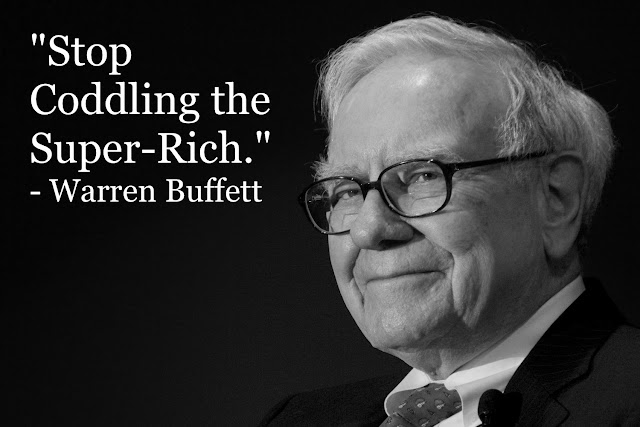

| Source: nytimes.com. |

5) Major sports programs are commonly linked to a culture of privilege and entitlement, which includes violence against women, a seriously underreported phenomenon, as the Florida State examples demonstrate. It might be convenient to presume that this is the isolated conduct of a few malefactors with a disposition to violence they brought with them to college, though it’s perhaps just as likely that they cultivated and extended the pleasures of domination and violence the sport teaches them and celebrates.

6) When football players at Northwestern initiated a unionization drive in order to protect themselves and their interests against their employer, the university, aided and abetted by the head coach, and concerned about possible repercussions to its bottom line, waged a concerted campaign to defeat them. To my knowledge, not one college or university president spoke in favor of the players’ autonomy and self-determination. Rather, they were determined to keep them in their properly subjected position.

Still, let us suppose, against the evidence, that Trustees and Presidents are serious when they talk about student athletes and seek to really fold sports into the intellectual life of a college or university. Well, here are some things they would do with respect to basketball.

For programs it will mean:

- no athletic scholarships will be granted;

- practices will be conducted and games will be played in only one semester; they will no longer encompass both fall and spring;

- regular season schedules will be limited to 20 games, roughly 1 and 1/2 per week;

- conferences will be realigned so that no road trip covers more than 200 miles and no flight lasts longer than 2 hours;

- no post-season conference tournaments are to be allowed; they are designed not for competition in a conference race but the gratuitous generation of revenue;

- the NCAA tournament will be reduced to 32 teams, which means the tournament can be completed in just over one week, minimizing the disruption to the end of the semester and final exams;

- no coach will be paid—from any and all sources—more than the median salary of an associate professor. Comparisons to CEOs notwithstanding, a coach contributes nothing to the university as a university; a coach is merely parasitic upon student-athletes.

- no morning practices before the first scheduled on-campus class;

- no practicing on weekends, when there generally are no classes; this is the time to study and rest;

- if students are expected to put in roughly five to six hours of work outside class per week, per course, basketball players will be allowed to practice no more than five to six hours per week; after all, they are not employee-athletes;

- should student-athletes leave before graduating to pursue a professional career, they will redirect 10% of the value of any NBA or European league contract they sign to their alma mater’s general scholarship fund.