William E. Connolly

Johns Hopkins University

The film, Melancholia, presents an attractive, young couple driving down a narrow, twisting, country path in a white, stretch limousine. Sunlight bathes a muddy roadway lined by bushes. The trip seems interminable to the viewer: that curve is too sharp, this zone is too muddy, those bushes are overgrown. Frustration and joy mingle in this scene, as the viewer oscillates between soaking in the beauty of that couple in a delicious setting and wondering when the stretch limo will reach a destination as yet unrevealed. We don’t know where they’ve been or where they are going, but we do smell trouble on the horizon.

Melancholia tracks beauty and denial, intentions and frustrations, glowing surfaces and opaque depths. . The couple turns out to be two hours late for their own wedding celebration at a sumptuous, well appointed mansion. She is received by friends and relatives as if her lateness and casualness about it are par for the course. The young woman is afflicted with melancholia. Each intention she forms is countered by an opposing tendency. She cannot act. Or, at least her planned actions are countered by enervation, and the impulsive acts she takes repeatedly hurt those around her.

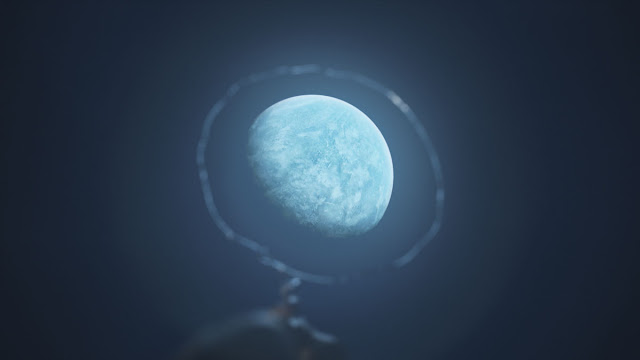

Two melancholias track each other in this film: her affliction and a planet called Melancholia. Previously hidden by the sun, this huge planet now circles ominously around the smaller earth, getting closer with each rotation. In one uncanny scene, after the wedding party has unraveled, two moons appear in the night sky, presenting a scene with two vanishing points instead of one. Up to this point people have reacted to the implacable event on the way with denial and forgetfulness. As the couple did in stretching out that drive. As these two moons bathe the world they bring the abstract prospect of the planet’s pulverization down to earth. How do you prepare for the end of the world? What about those children who have just begun to form skills, ambitions and hopes? It is enough to make a therapist, a priest, or a philosopher stutter.

Yes, death is terrible. Your mother’s death, for instance, filled you with grief. A life lived in work, commitment and turmoil, brought to sudden termination. Gradually, you also come to terms with how several memories have lost some solidity with that death. You and she shared, say, a secret that those childhood humor-fests that got you into trouble with teachers were subtended by a personality too feminine and sensitive to be acknowledged in the rough and tumble of boyhood life. No one shares that secret now. Unspoken features of her life, expressed in her demeanor, have become sealed too. Suppose something wonderful happens to you. The impulse to share it is countered by a sudden recollection that is too late to do so. The losses of death return. Death teaches those left how deep memory runs and how fragile its depths are.

A massacre, a holocaust, a massive bombing. These are even more implacable. They break the bond of trust in the world that had tacitly bound survivors to it. These shocks and losses are so horrifying that some survivors never heal. Healing may be felt as disloyalty to those who were slaughtered through an unspeakable breach of trust. Unremitting despair or revenge settles into life. How could the world encompass such acts of mindless violence?

Melancholia has yet different fish to fry. Not death. Not a holocaust. But an impersonal collision between two planets, at least one of which houses adult human beings, ants, children, hippos, crocodiles, rainforests, films, the internet, TV melodramas, wedding parties, semi-sovereign states, steamy love affairs, rich intellectual traditions, academic quarrels, military adventures, holocausts, an ocean conveyor belt, Picasso, species’ evolution, volatile weather systems, multiple gods, and basketball. No more games. No new loves, long slow runs, intellectual traditions. No future horizon. No artistic contribution to sensitivity, enriching feeling and perception. No one will remember anything after this collision. How do you respond to that?

Some devotees to monotheism conclude that an omnipotent, benevolent God makes such an event impossible. Other devotees incline close to the theme of Melancholia before veering off radically. They envisage Armageddon, in which a few are lifted to heaven and billions of nonbelievers are punished with the infinite hell of sulfur and fire. Is there, circulating somewhere in that punitive story, an initial identification with humanity as such? Perhaps. Otherwise the demand to punish so many would not have to be connected to the image of such a vengeful God. When I read The Book of Revelation, as I do regularly in an undergrad class, I sense an initial identification with the human estate that is overridden by a desire to take revenge against a large slice of humanity for features of the human condition that exceed our control. The brilliance of Melancholia is that it peels away the issues of responsibility and existential revenge to allow the experience of attachment to soak into our pores.

Those who project neither an omnipotent nor a punitive God into being, sometimes focus on our attachments to the human estate as such. They may be theists or nontheists. Such a sense usually hums in the background of everyday life, crystallized periodically through artistic work and existential threats. Melancholia dramatizes a sense, already woven into life, that humanity matters to us immensely. It matters in part through connections we have to other humans, past and future, and in part through our affinities to nonhuman beings and processes of indefinite variety. We do not face the probable prospect of a collision between planets in which everything is pulverized, though the possibility of an asteroid shower or huge volcano is nothing to sneeze at. We do face a variety of ecological and military dangers that, if enacted, could radically transform human life on the face of the earth. We both sense these dangers and feel pressure to divert attention from them.

Much of life is organized around daily routines and struggles that distract attention from larger attachments. Such routines are not to be denigrated; they form part of the fabric of life. Even denial and deferral harbor some degree of rationality, since total immersion in the dangers of the future leads to a neglect of daily duties and needs. Still, such routines can be re-enforced too much, to divert attention from dangers that no individual, family, locality, or state can resolve alone. The world, today, is replete with ideologies that ridicule folding a sense of the fragility of things into parochial interests, identifications, and practices of responsibility. Watch Fox News more often to see how this ridicule works.

As abundantly clear, I am a critic of what might be called, in honor of Charles Taylor, “exclusive humanism”. To him, that is the dangerous idea that humanity is sufficient to itself, without God. As I rework the theme, exclusive humanism expresses the idea that humanity is unique, either in itself or in its unique relation to God. Only we matter, because only we embody reason, or language, or consciousness, or reflexivity, or God, or a long time horizon. But we are not unique; we are merely distinctive. Most things about us commonly treated as unique are either profoundly contestable (e.g., the ideas of God and a naturalistic universe) or shared to varying degrees with other beings and things. Bacteria, for instance, pursue simple desires and ends, though ours are more reflexive. Moreover, we could not be human in the absence of innumerable nonhuman entities within and outside our bodies, including bacteria and viruses. Many become infused into our neurons and viscera helping to constitute their performances. Everywhere you turn such connections abound. To be attached to humanity is to be attached to a variety of other things.

Exclusive humanism is a dangerous conceit. Seeing that, we feel how the call to stretch our awareness, sensitivities and attachments by artistic means is acute. Transcendental arguments that purport to set strict, universal limits to human understanding and sensibility must be resisted in order to stretch and revise that species provincialism in which the Euro-American world has been stuck for so long.

However, to act as if there is no species priority falsifies much of experience and pulls attention away from those artistic explorations, role experimentations and political militance that deepen the attachment to the human estate as they also broaden our appreciation of debts, affinities, dependencies and symbiotic relations with other things. So, the terms “anti-humanism” and “post-humanism” leave me cold, too. They do challenge the excesses of classical humanism—a good thing. But they too readily leave the impression of giving no ethical priority to the human. E coli is a bacteria to defeat. Climate change is something to reverse by radical action if possible, for us and the processes to which we are connected.

The problem is that neither theistic nor nontheistic sources of attachment to the future of the human estate have proven to suffice. These connections must be dramatized and cultivated more actively, as we seek new ways to diminish the priorities constituencies give to the short over the long term and to close over broad identifications. It is unwise to eliminate the former tendencies because a parent must give some priority to its children, a teacher to its students, a consumer to its needs. But many forces conspire today to render short term and close identifications too exclusive. Our practices of production, consumption, investment, teaching, and spirituality engender such closures. And the prevailing ideologies of today, led by neoliberalism, exacerbate those very tendencies. We must expose the simplicities, dangers, and conceits of these ideologies, as we work to stretch our perceptions, experiment upon role expectations invested in us, and up the ante of political militance. I continue to think that it is wise to set a simultaneous general strike in several countries as a beacon to pursue over the next few years.

.jpeg)